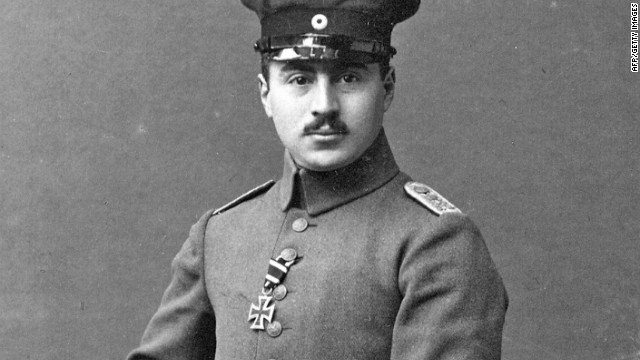

This image dated around 1918 shows Ernst Hess, a judge at the district court of Duesseldorf, western Germany.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- The Jewish Voice from Germany newspaper unearths internal Nazi files on Ernst Hess

- Hess served in Hitler's infantry unit in World War I but didn't know him, then was a judge

- A 1940 order saved Hess, despite his Jewish heritage, "per the Fuhrer's wishes"

- The order was revoked the next year, and Hess ended up in Nazi concentration camps

(CNN) -- An estimated 6 million Jews died at the

hands of the Nazis and their allies during the Holocaust. Hundreds of

thousands more suffered, but somehow survived, in concentration camps.

And some escaped, savoring freedom they otherwise never would have

known.

Then there's Ernst Hess,

who was a decorated World War I soldier, former judge and, despite being

raised a Protestant and marrying someone of that faith, a "full-blooded

Jew" in the eyes of the Nazi regime.

According to a

groundbreaking report, Hess was granted a reprieve despite this

designation thanks to none other than Adolf Hitler.

Susanne Mauss, editor of the Jewish Voice from Germany

newspaper, found the August 27, 1940, note from the Gestapo (the

infamous Nazi secret police) that saved Hess -- albeit temporarily. The

order was revoked the next year, and Hess spent years doing hard labor

in Nazi concentration camps and work sites.

Still, given Hitler and

his colleagues' extreme views and actions on Jews, even the temporary

amnesty granted in the letter that Mauss unearthed in a file kept by the

Gestapo in Dusseldorf about Hess is extraordinary.

Written by the notorious

SS figure Heinrich Himmler, the note calls for saving and protecting

Hess "as per the Fuhrer's wishes," referring to Hitler, who had led

Germany since 1933.

The slave workers were forced to live outdoors and were treated terribly, and of course they were watched by members of the SS

Ursula Hess

The letter, a copy of

which is posted on the Jewish Voice from Germany's website, also states

that Hess should not be inconvenienced "in any way whatsoever."

Hitler and Hess had

crossed paths before, serving in the same infantry unit during World War

I. In fact, for a short time Hess had been Hitler's commander -- though

the Jewish Voice from Germany said Hess, whose now 86-year-old daughter

was interviewed for their story, didn't personally know Hitler and

their fellow comrades described the future Nazi leader as quiet, with no

friends in the regiment.

But Hess himself was

close to many of his fellow veterans, including Fritz Wiedemann,

according to daughter Ursula Hess. And Wiedemann, who became a top aide

to Hitler from 1934 to 1939 before becoming Germany's consul in San

Francisco through 1941, helped connect Hess to Hans Heinrich Lammers,

the head of the Reich Chancellery during Hitler's reign.

Hess, who was forced to

retire as a judge in 1936 -- the same year he was beaten up by special

police in front of his home -- had pleaded for leniency before.

According to the Jewish Voice, he had petitioned Hitler to make an

exception because his daughter Ursula would be considered a

"first-degree half-breed" under Nazi doctrine.

Highlighting his

patriotism and Christian upbringing, Hess wrote, "For us, it is kind of

spiritual death to now be branded as Jews and exposed to general

attempt."

That appeal was denied,

though the Hess family was able to move to a then German-speaking part

of Italy for the next several years. In that time, Hess still got part

of his military pension and his passport wasn't stamped with a red J to

brand him as Jewish, the Jewish Voice reported.

But after a pact with

Italy that ceded that area to the Nazi regime and the family's attempts

to flee to Switzerland and Brazil failed, they landed back in Germany in

1940.

The reprieve, credited to the fuhrer, came in the summer of that year.

But in 1941, Hess

submitted the letter of protection, only to have it swiped away. The

special order revoked, he landed soon thereafter in a concentration

camp, and then began working for a timber processing company helping

build barracks for Nazi soldiers.

"The slave workers were

forced to live outdoors and were treated terribly, and of course they

were watched by members of the SS," said Ursula Hess of her father, who

besides being a soldier, judge and "sportsman," had once been a concert

violinist. "Had he not been as fit as he was, he would never have

survived."

The name Hess is well

established in German 20th-century history. A man also named Ernst Hess

was one of Germany's ace fighter pilots during World War I, before being

killed in action. Rudolf Hess was once Hitler's deputy, before flying

to Scotland on an alleged peace mission in 1941 that instead ended with

him becoming a prisoner of war.

Ernst Hess, though, was a

prisoner of a very different sort through the early 1940s when Nazi

authorities deemed him "a Jew like no other."

When the war ended and

he gained his freedom, according to the Jewish Voice report, Hess was

asked to become a judge yet again. He turned down the offer. A year

later, Hess launched a new career and gained new prominence as a railway

executive.

By then, he'd rejoined

his wife and daughter. But not all his family: His sister Berta was

killed in 1942 in the Auschwitz concentration camp.

0 comments :

Post a Comment